by Don Sawyer

Although absurd in a couple of pages to attempt a history of the American diner, let alone examine the evolution of hamburger haunts, hot dog havens, and drive-in restaurants, a cursory overview will help articulate my artwork. I would encourage you to reference the “bible” of diners—Richard Gutman’s The American Diner Then and Now (Harper Perennial), Jim Heiman’s Car Hops and Curb Service (Chronicle Books), and regional treatises like Randy Garbin’s Diners of New England (Stackpole Books), all from whom I freely borrowed below. Most essentially, treat yourself to your local diner or roadside eatery. Slurp the joe, wolf the waffles, converse with the counter crew. Your neighborhood diner is more than an idealized hunk of Americana; it’s a human harbor in a frenzied world-sea that needs you to help define and sustain it.

In 1872 a Providence, Rhode Island entrepreneur named Walter Scott modified a horse-pulled wagon to serve sandwiches, boiled eggs, pies, and coffee to late night street denizens and shift workers. So rough were his patrons that he often confiscated their hats as collateral or demanded payment with a club. Still, business boomed. Soon Scotty had copycat lunch wagon competition locally and in Springfield-Worcester, Massachusetts. Patents were granted for lunch car design and construction, one issued to a Worcester wagon-owner named T.H. Buckley, who realized that it was far more profitable to build these lunch cars than operate them. Buckley is thus acknowledged as the progenitor of the American diner and the father of the famous Worcester Lunch Car Company. His wagons were characterized by large wheels to negotiate cobblestones, overhangs to keep patrons dry, barrel roofs, ornate murals and lettering, frosted glass, shiny fixtures, and rudimentary ice boxes and cook-stoves.

In the early 1900’s, three lunch wagon companies dominated— Worcester Lunch Car, Tierney, and O’Mahony. Their products were measurably larger and more self-inclusive, with smaller wheels, lengthy counters, mid-side entrances, tile work, porcelain panels, and—thankfully—bathrooms! Although they continued to cater to “nighthawk” patrons, many lunch cars assumed permanent locations, thereby gaining daytime commerce and respectability. New companies like Bixler, Brill, Pollard, Sterling, Wason, and Ward & Dickinson evolved. Further styling was borrowed from the railroad’s Pullman dining cars, birthing the term “diner.” During this period, women were invited to dine in, probably more for economic gain than social equality! In fact, the prefix “Miss” was added to many diner titles to soften, feminize and gentrify popular lunch car image.

Simultaneously, Main Street America was changing, in great part because of Henry Ford’s quest to wrap a sedan around every worker. Road construction burgeoned and famished travelers needed sustenance en route to work or play. Merchants responded with food stands, at first unimaginative and crude but later colorful and whimsical, with animate facades, catchy motifs and bold signage. Famous road stops like the Texas Pig Stands and California’s Tam O’Shanter provided drive-up parking. Curb service was born (anecdotally, all early carhops were male, referred to as “tray boys”). Many food stands became standardized, then duplicated in appearance, service, and drive-in potential. Thus, the term “drive-in” was added to popular lingo, and theme stands like A&W, White Tower and White Castle sprouted everywhere.

During the Depression, large complex diners were simply too expensive to build, so a new business of repairing and modifying existing diners blossomed. Small diners like Kullman’s “minis” and the Hickey/Gemm “dining carts” appeared everywhere. These eight-to-ten-seat dining carts were often trailered or placed on flatbed trucks and carted daily to specified sites, just as Walter Scott did with his lunch wagon decades before. Similarly, drive-in restaurants survived the Depression because of their affordable menus, convenient locations and wholesome atmosphere. New drive-ins were simple and boxy, but people came for good cheap food and fun.

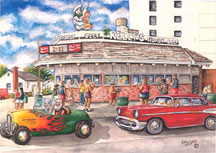

In the 1930’s the world went Deco-crazy, and the American drive-in reached its pinnacle. Swirling, modernistic, futurific lines and colors dominated. Drive-ins became fantastical, even outlandish: some were octagonal or cylindrical; others were imbued with silly themes (like windmills or airplanes); yet others were downright garish because of excessive use of newly introduced neon. Lounge sections were added. Women became valued workers, often clad in campy uniforms and roller skates. Menus were expanded to include fish, vegetables, and desserts. So popular were drive-ins that at one point there were over 200 in greater Los Angeles alone!

Diners during the 30’s and into the 40’s became sleeker and streamlined. New-look diners like Sterling Streamliners featured space-age lines and bullet-shaped ends. Glass blocks, Formica surfaces, stainless steel and stylized lettering snagged the eye. “Terra Cotta” (flat porcelain panels) and “fluted” (tubed) porcelain ruled the day. Vaunted diner-makers like DeRaffele, Fodero, Mountain View, and Paramount were popular as World War II neared.

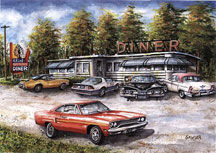

During World War II, sugar, milk, meat and other staples were in short supply, along with construction materials and male labor. Diner building slowed and menus were pared. Women became essential counter employees (spawning the stereotyped caustic-but-caring “Flo” we admire today). After the war, diners boomed, with many prior foremen venturing off on their own to form companies like Comac, Manno, Master and Supreme. Booths were added, corners were “softened,” and new products like Formica, steel tubing and Naugahyde replaced expensive materials like marble, leather, and mahogany. Homemade diners appeared everywhere, many actually encased in stainless to emulate prefab diners.

Sadly, the spirited 60’s inhibited the American diner. Fast food meccas with their prompt, cheap, predictable menus were more appealing to scurrying commuters and urban sprawlers. Diners suddenly seemed tired obsolete relics; in fact, some diner owners became embarrassed, literally bricking in or stuccoing over their dining cars. Many new diners of this era, like the mistitled “Colonial” diners, bore no resemblance to their noble glistening forerunners. They featured brick arches, flagstone faces, sharp corners and mansard roofs, looking more like large Mediterranean family restaurants.

Drive-ins, too, succumbed to mechanized, homogenized food chains. Curb service and “hanging out” were less desirable than swift service, minimized menu, and paltry prices. Contrary to popular image, rock-n-roll teenies in hot cars actually brought little financial reward to drive-ins. Moreover, rising real estate prices inhibited private restaurant investment, and expanding highways began to consume available Main Street lots. Of the thousands of once ubiquitous American drive-ins, only the Sonic chain, a few A&W’s, and a handful of individually owned “retro” drive-ins remain.

Fortunately for us, a deep appreciation for classic diners was rekindled in the ‘90’s and exists today. There is widespread effort to restore and preserve these historic gems. Clearly the front-porch/diner/drive-in image of an earlier, kinder America makes us feel good, and safe . . . as if we belong and are valued. Diner-makers seem to agree. Several companies like Kullman and DeRaffle survived to build beautiful imposing diners today. Others like Diner-Mite and Starlite have entered the market with colorful reproductions.

When I began painting diners three decades ago, I was nervous. Who would my patrons be? Would only geriatric, mill-working fellow-curmudgeons who ate at diners out of necessity buy my work? I continue to be amazed. Everyone buys my art— old, young, male, female, blue collar, professional, serious, light-hearted! After all, everyone is welcome at the diner . . . and everyone is needed to give the diner its unique atmosphere, spirit, and folklore. I thank you for your interest in my “road art.” Perhaps we can meet sometime, you and I, to share a conversation and a cuppa joe at the counter, a caustic-but-caring waitress named “Flo” nearby!

Curtis's Barbecue, Putney, Vermont

Site design © Coffee Cup Media LLC.

All art prints and text © Don Sawyer and may not be reproduced in any form without consent.

207-353-5162

41 Deervale Rd

Durham, Me 04222

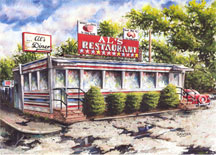

Al's Diner, Chicopee, Mass.

Capitol Diner, Lynn, Mass

White Hut (one of my favorite hamburger havens, this 1939 joint is still jumping!)

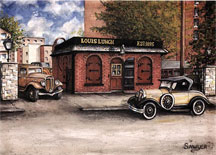

Louis Lunch, New Haven, CT

Lawton's Hot Dogs, Lawrence, MA

Gilley's Lunch Wagon, Portsmouth, NH